CUBE is a lightweight, portable, and scalable multi agent environment that unifies symbolic reasoning with embodied interaction. Agents operate in a shared grid world and must push weighted blocks into a goal zone while avoiding collisions, congestion, and unproductive block chains. These spatial dependencies make cooperation necessary and observable.

At its base level CUBE is built on the PettingZoo parallel API, so it can plug directly into

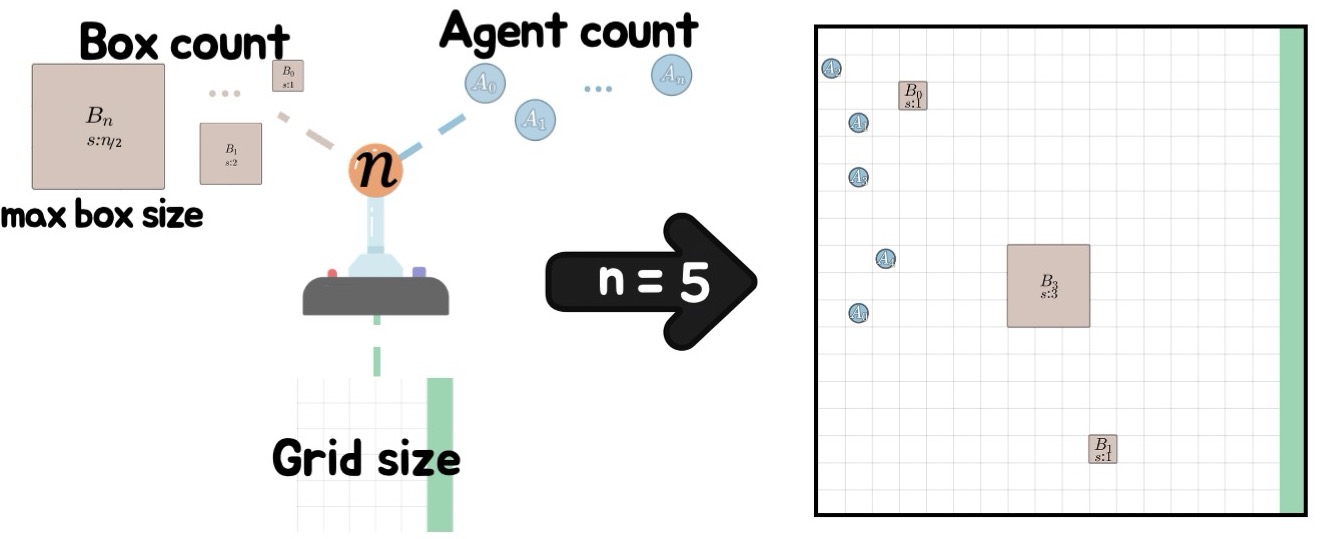

existing multi agent reinforcement learning pipelines. The default episode configuration is generated

automatically from a single integer n. The grid side length is

k = max(20, n), there are n agents, and blocks have integer weights from

⌊n/2⌋ + 1 down to one, with lighter blocks appearing in greater numbers. Roughly half of the grid

is covered by blocks. Agents start along the wall opposite the goal region, and blocks are placed away from

walls and corners so that every block is movable by pushing.

The parameter n therefore sets both environment scale and cooperative difficulty.

As n increases, heavier blocks require larger agent quorums and more complex block chains,

and congestion grows since each agent contributes only unit force. Tasks at the same n have

comparable complexity, which supports fair comparison of cooperative strategies across methods.

n sets grid size, agent count, and block distribution.

Larger n increases the effort required for cooperative success while keeping

difficulty predictable and reproducible.

CUBE is presented with four main contributions.

n that enables systematic study of cooperation across comparable difficulty levels while

still allowing custom scenarios.

Traditional reinforcement learning benchmarks emphasize low level action spaces and scalar rewards. These signals are useful for gradient based training but give little support for symbolic reasoning, interpretability, or debugging. For LLM agents, emitting long sequences of primitive moves and waiting for numerical rewards is unnatural and inefficient.

Symbolic planning domains have clear preconditions and effects but usually assume deterministic transitions and ignore embodied dynamics such as collisions, congestion, or force accumulation. They are therefore not enough on their own to study embodied LLM agents that must reason in uncertain, interactive worlds.

CUBE bridges this gap by wrapping primitive block pushing actions into a symbolic vocabulary and linking that vocabulary to an embodied grid world. This lets LLM agents plan using interpretable, compositional actions while still having to cope with uncertainty, races for cells, and changing geometry.

Human reasoning blends symbolic and embodied perspectives. We imagine plans, act, compare outcomes with expectations, and revise our internal models. CUBE is built to support a similar loop for LLM agents. Plans are expressed in symbolic actions, executed as primitive moves, and evaluated with both scalar and structured feedback.

Embodied constraints keep tasks challenging as team size increases. Moving any block or agent reshapes the scene. Agents must cope with tasks that can disappear, delivery paths that become blocked by other blocks, and sequences where one agent can temporarily make a block unreachable.

This makes CUBE a natural testbed for research on cooperative intelligence at scale, including communication, task allocation, and group level planning.

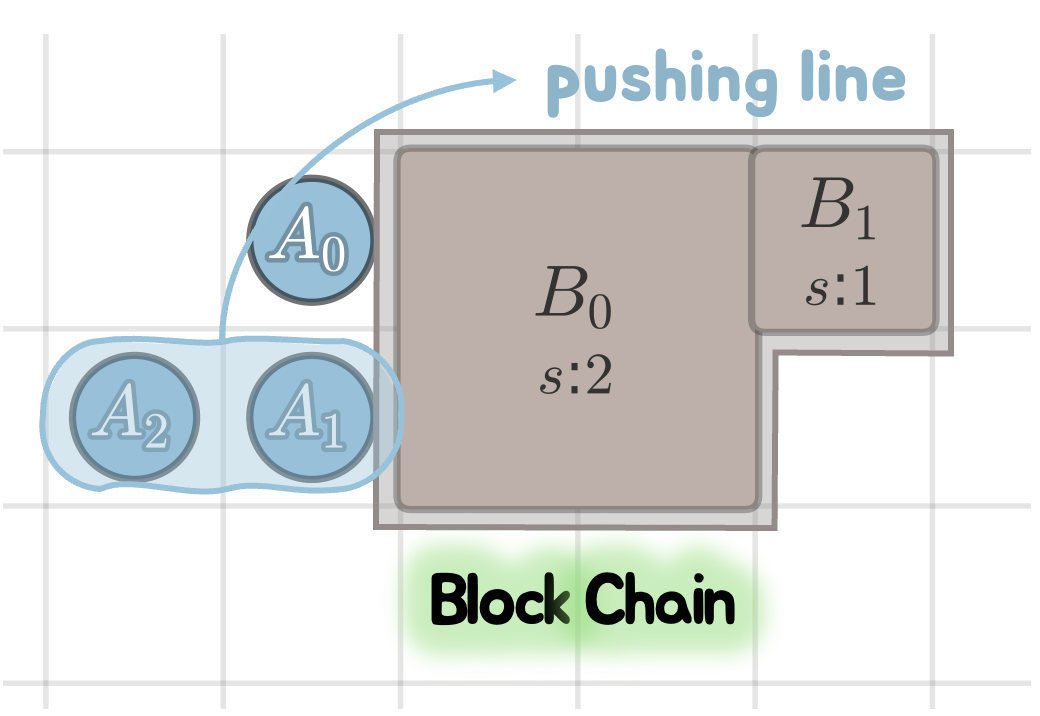

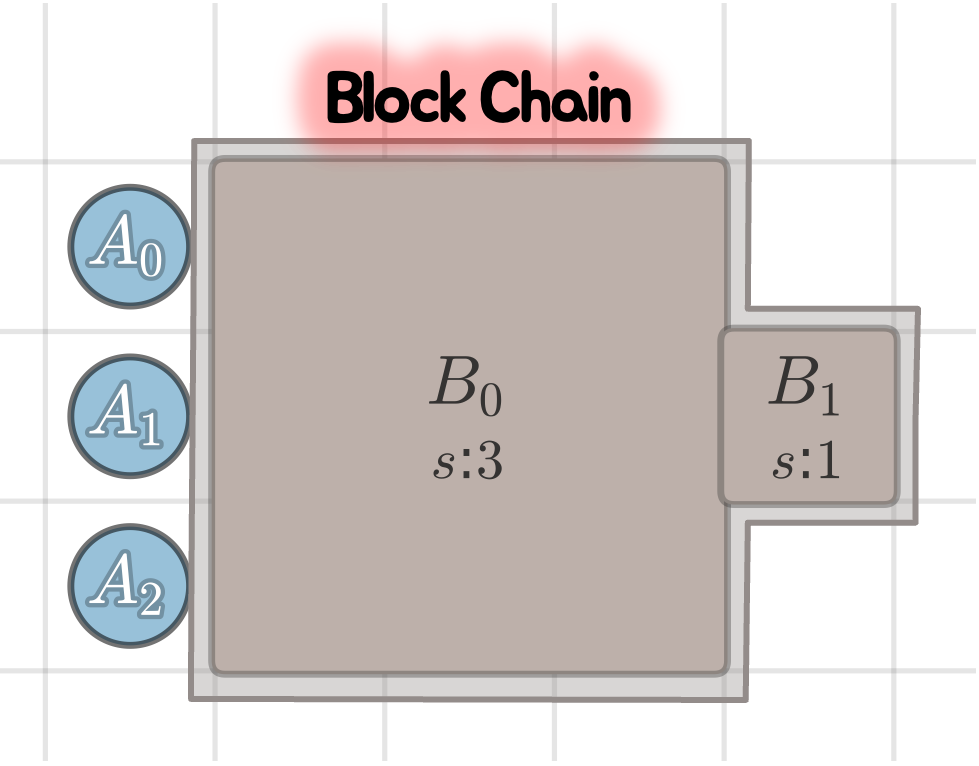

Agent chains, block chains, and forces in CUBE.

Symbolic actions unfold into sequences of primitive movements that operate on the shared grid.

CUBE exposes two complementary observations.

The action interface has two layers.

{STAY, UP, DOWN, LEFT, RIGHT}.

Movements succeed only when the target cell is free, and pushes succeed only when aligned agents

provide enough force and the front cell is empty.

move, move_to_block, rendezvous,

push_block, yield_block, idle,

and wait_agents. Each action compiles to primitive moves until a condition is met.

Agents submit short plans that are sequences of such actions with arguments, which then execute in order.

CUBE provides both scalar rewards and a library of symbolic concepts that help define custom metrics. The default reward has a small step cost and a shared delivery reward proportional to delivered block weight. Symbolic concepts include utilities such as functions that measure distances, count aligned agents, summarize block progress, measure quorum deficit, and detect blocking, which can be combined to design adaptive feedback or evaluation signals.

In CUBE, blocks can form chains that require joint force from several agents. A pushing line forms when agents align along a block face, each contributing unit force in the push direction. Motion succeeds only when the total applied force meets or exceeds the chain weight and the frontmost destination cell is free.

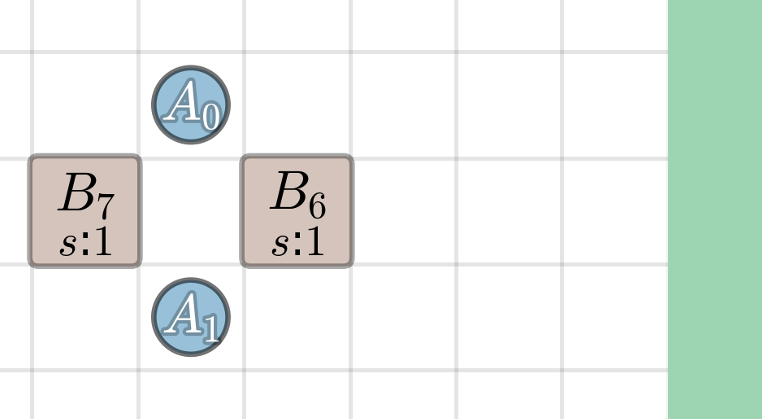

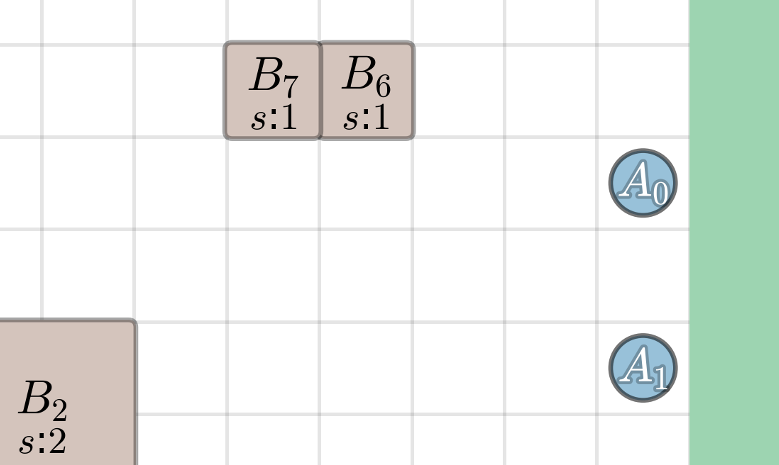

Valid tasks can disappear dynamically as blocks move. For example, a face of a block that was previously reachable can vanish when another block moves adjacent to it. Agents that were committed to that face must then recover and replan. Cell races and boundary geometry introduce further failure cases, such as blocks that become actionless along walls because they can only be pushed, not pulled.

Successful chain. Aligned agents form a stable pushing line and move a composite block chain.

Geometric failure. Misalignment or an occupied destination cell prevents progress.

Failure I. Agents cannot stage on the target face due to congestion, so no joint push can form.

Failure II. Agents block one another or oscillate, preventing stable cooperation despite a feasible strategy.

A single integer n controls the entire task family.

k = max(20, n).n agents placed along the wall opposite the goal region.⌊n/2⌋ + 1 down to one, with lighter blocks appearing more often.

Larger n increases both congestion and the quorum needed to move heavier blocks.

Layouts at a fixed n differ but have similar cooperative complexity, which provides

a clear curriculum from small groups to large teams.

Grid size, agent count, and block distribution scale with the curriculum parameter n.

The heuristic baseline follows a greedy strategy.

At each stage it selects the block closest to the goal zone and assigns agents to move it,

issuing symbolic instructions such as move_to_block, rendezvous, and

push_block until the block is delivered. The baseline produces valid cooperative

behavior without explicitly optimizing path length or resolving congestion, and serves as a

reference point for more advanced agents.

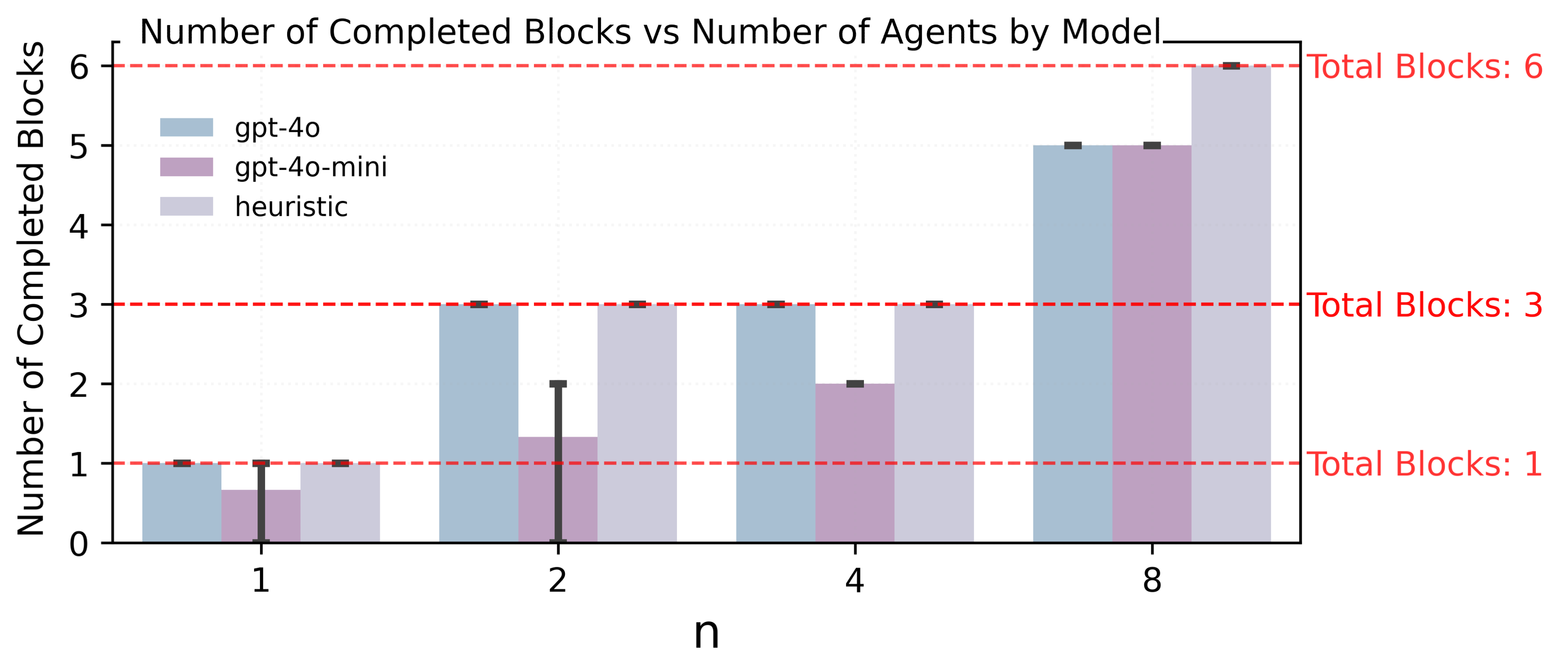

Number of completed blocks versus agent count n for language agents and the heuristic baseline.

As language based baselines, the paper evaluates two LLM agents in a zero shot style setting. Each agent repeatedly receives a symbolic observation and generates short plans written in the CUBE action vocabulary, with a prompt that encodes a simple rule to always target the block closest to the goal zone.

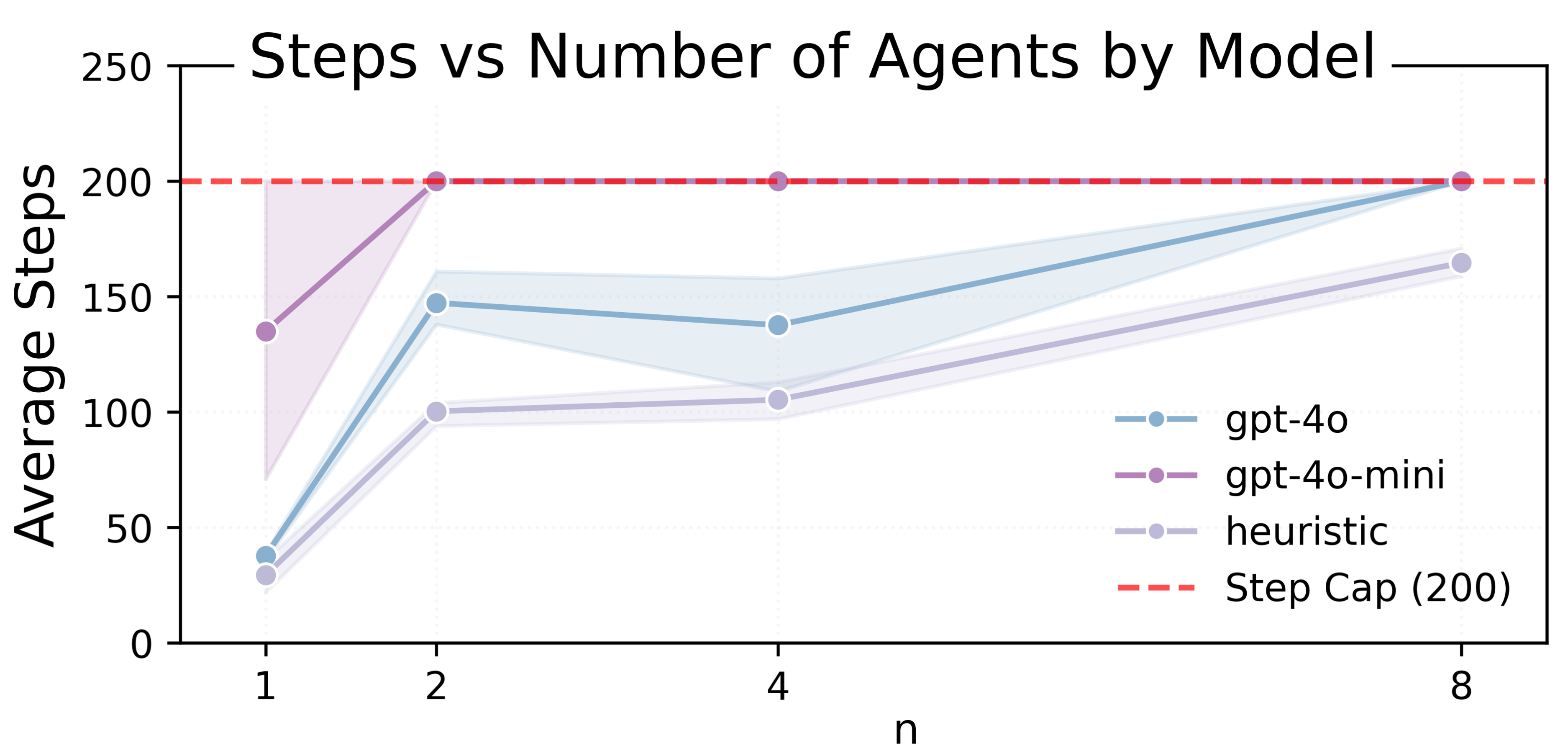

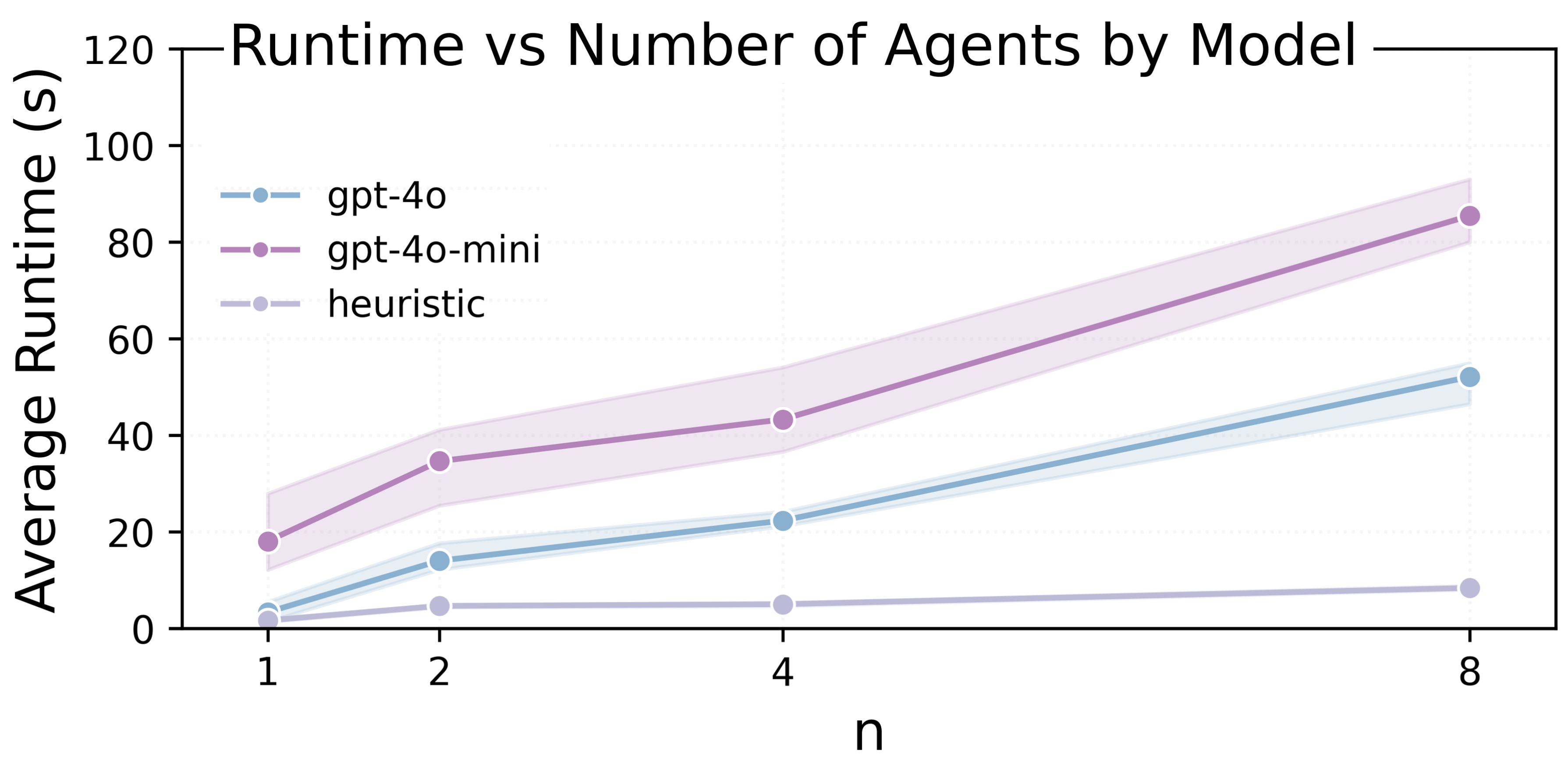

These naive LLM agents can generate executable plans but perform inconsistently, particularly when they must rely on other agents. Smaller models show high variance and longer runtimes, suggesting frequent replanning and difficulty with coordination as n grows.

Average steps per episode as n increases (capped at 200 steps).

Average runtime versus n by model, highlighting that LLM inference dominates runtime.

Overall, the heuristic baseline consistently completes all blocks at the tested scales, whereas naive LLM agents reveal a cooperation gap. They can express nontrivial symbolic behavior yet fall short of robust cooperative performance as team size grows. This motivates richer designs for embodied LLM agents that combine symbolic world models, communication, and learning.

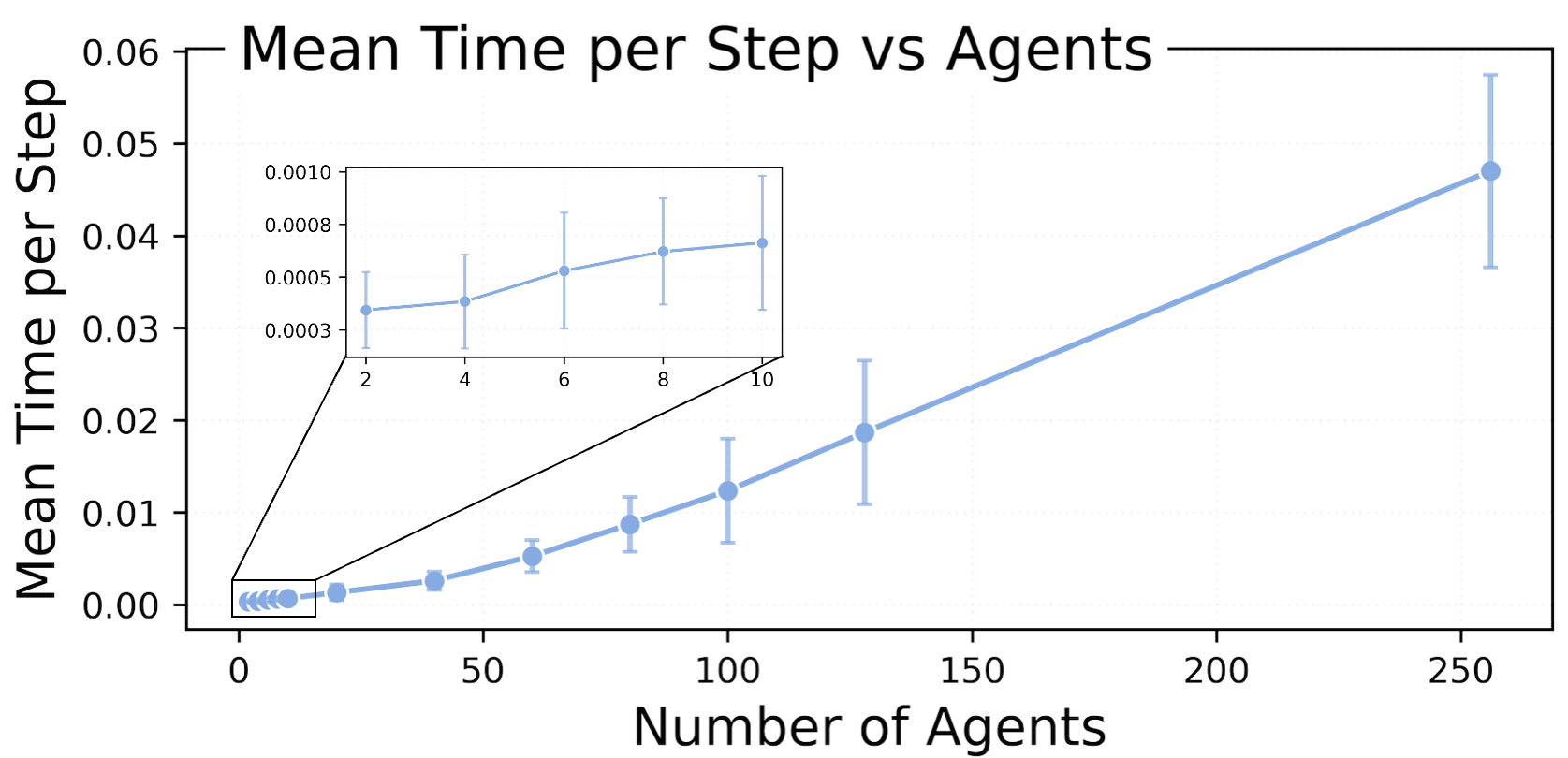

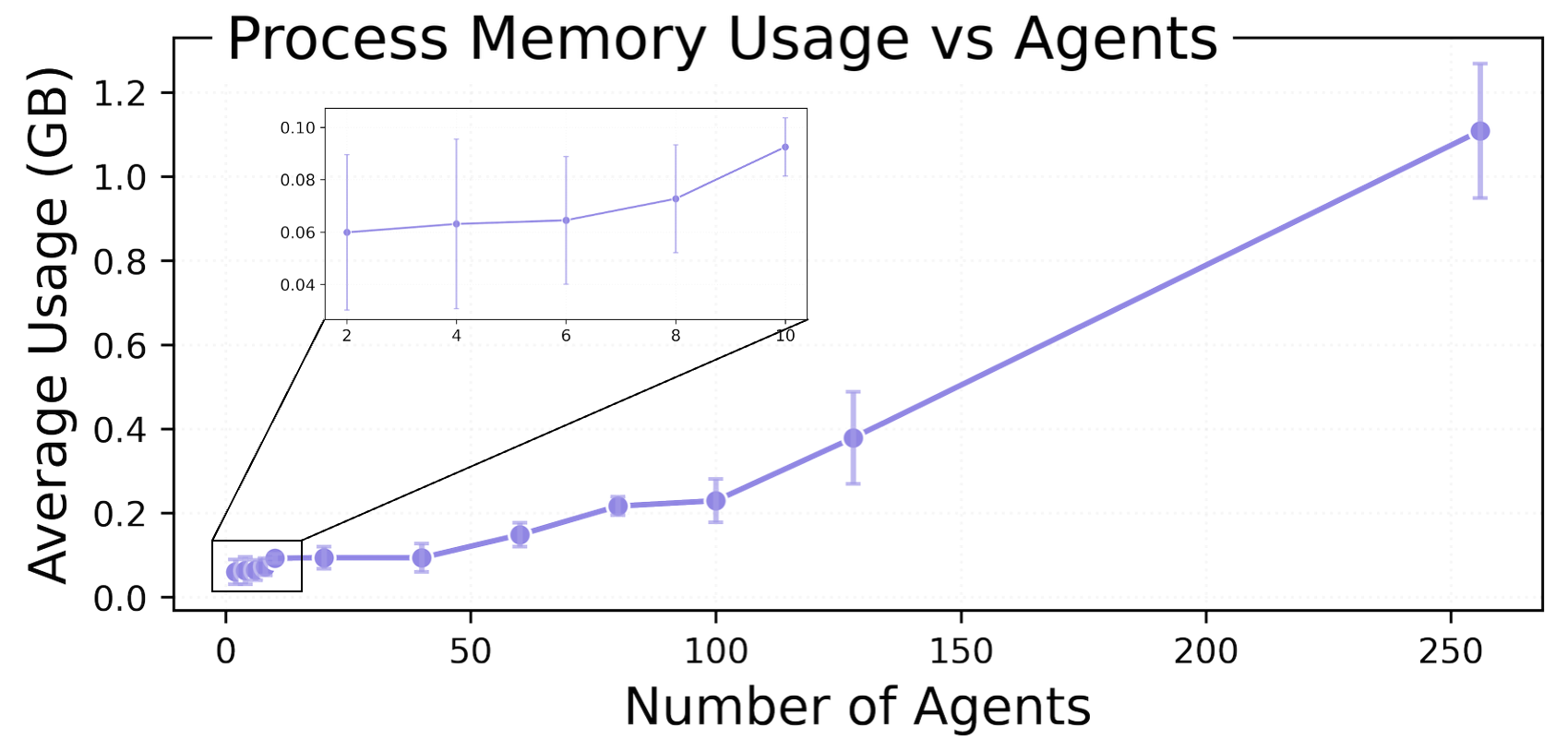

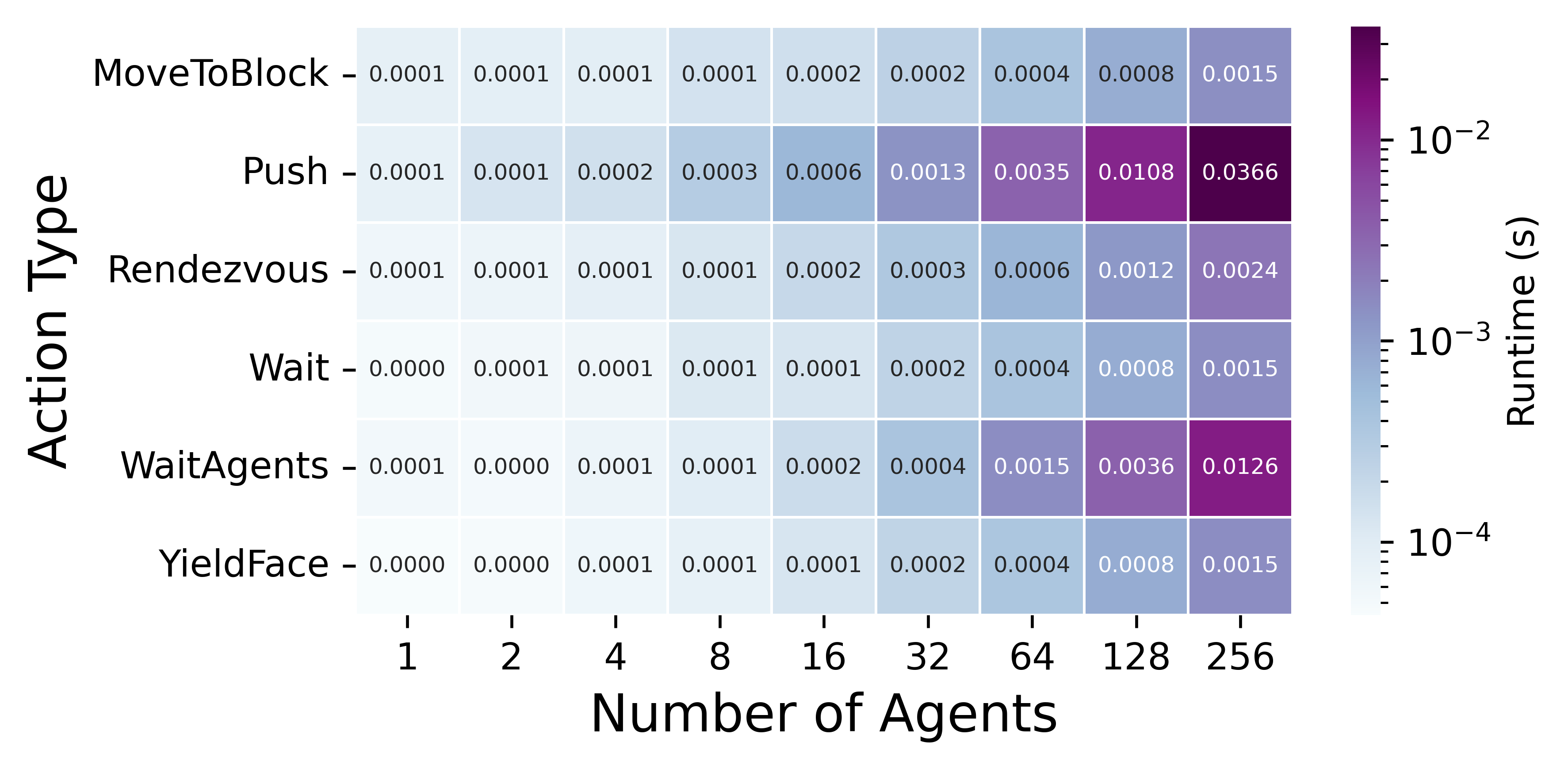

Mean environment step time grows smoothly with n, from small fractions of a millisecond for small teams to tens of milliseconds at 256 agents on one CPU core.

Memory usage increases approximately linearly, reaching under a gigabyte at n equal to 256, with tens of megabytes at small scales.

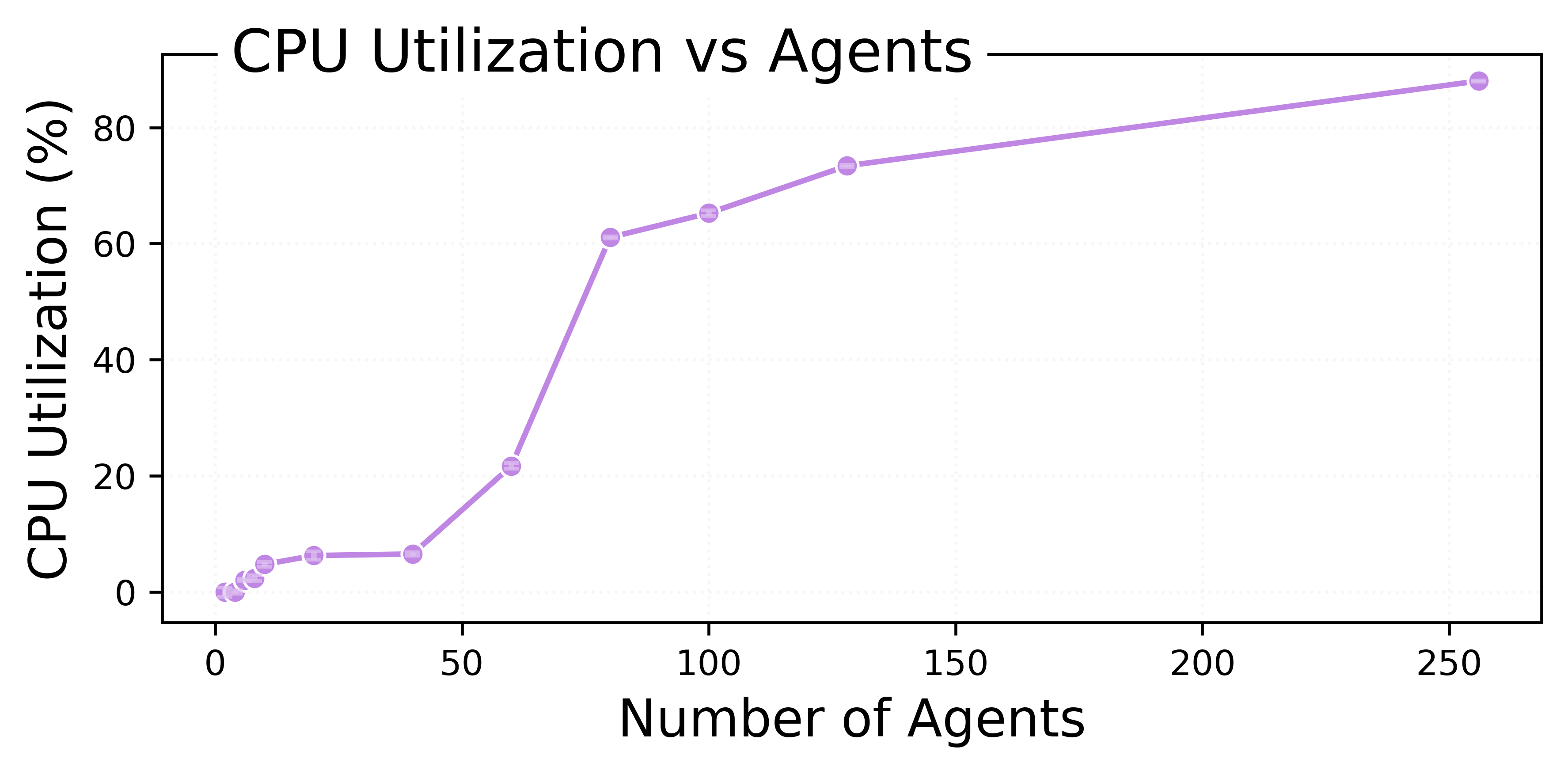

CPU utilization rises steadily and stays within a manageable range even with 256 agents, so the environment remains lightweight compared with LLM inference.

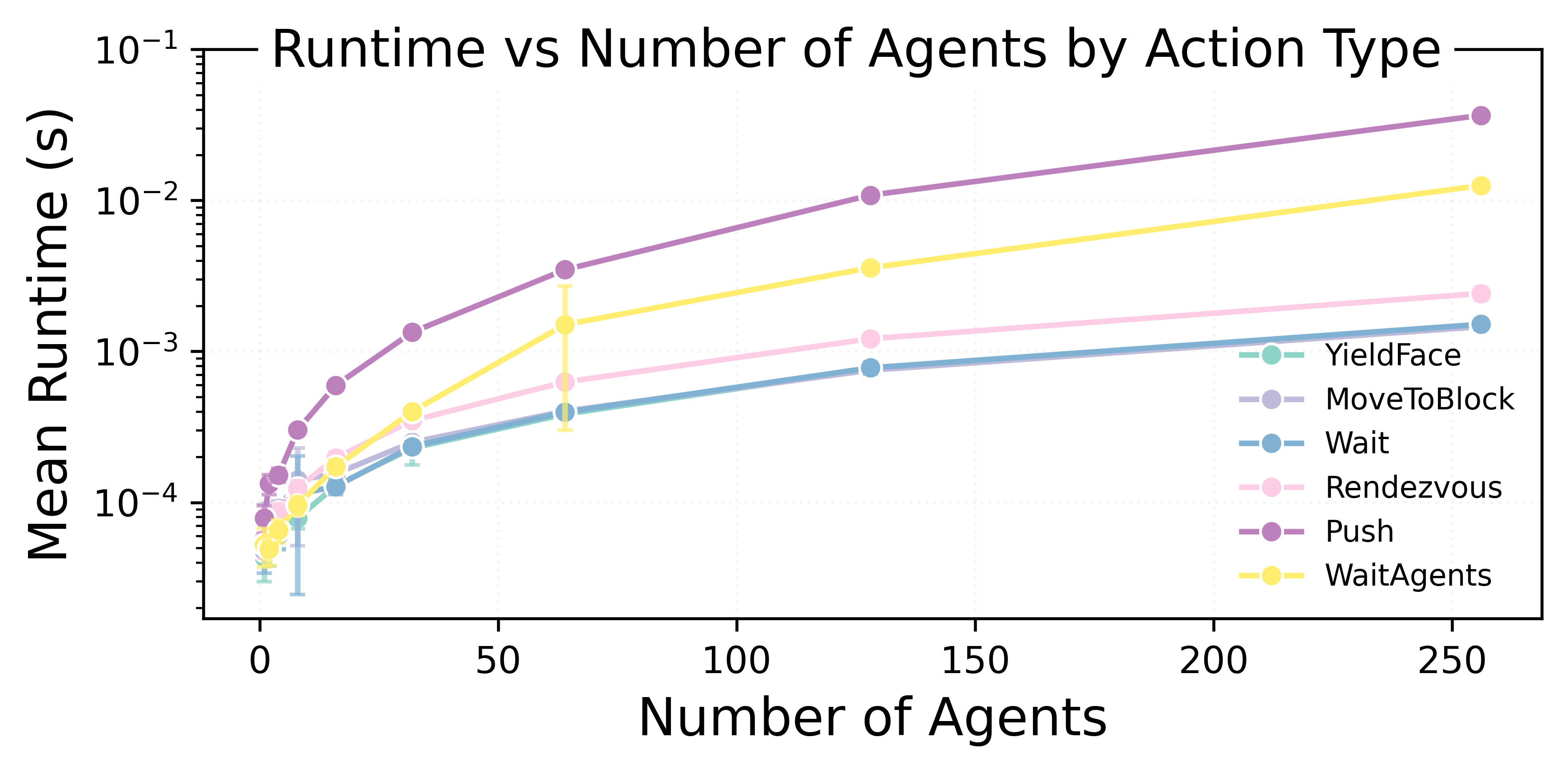

Mean runtime per symbolic action versus agent count. Most actions stay in a narrow band of run times even at larger n, while actions that inspect many environment objects become more expensive but remain efficient.

Heatmap of symbolic action runtimes across scales.

In contrast, LLM inference time is relatively large. Generating even short plans takes hundreds of milliseconds to seconds, which makes environment overhead negligible for studies of embodied language agents.

As agents move blocks they create new chains, tighten corridors, or close off some paths, which can make later deliveries easier or harder. Agents must reason about how current choices change future task difficulty and may need to revise decompositions on the fly.

Successful teams need to understand how blocks interact, which sides can be used for approach, and how block chains create soft dependencies between tasks. Simple distance based rules are often not enough when heavy blocks and narrow passages interact.

Many pushes require several agents to reach specific faces of a block at similar times. Rendezvous and waiting behavior must be coordinated with path planning and congestion, and agents need to recover when timing assumptions fail.

Agents rarely know exactly what teammates will do. They must form expectations about others, infer goals from movement, and decide when to wait, yield, or reroute. Misjudgments can lock tasks temporarily, such as when a single agent stands in the only useful staging cell near a block.

Agents may execute plans with different horizons and therefore fall out of sync. Centralized planners, decentralized policies, and communication protocols all have to cope with this asynchrony and design strategies that are robust to partial or delayed execution.

CUBE opens space for methods that blend symbolic world models, model predictive control, multi agent reinforcement learning, and LLM based planning. It also supports comparison between centralized planners and decentralized designs that rely on communication, emerging conventions, or shared tools for cooperation.

@inproceedings{yangcube,

title = {CUBE: Collaborative Multi-Agent Block-Pushing Environment for Collective Planning with LLM Agents},

author = {Yang, Hanqing and Nourzad, Narjes and Chen, Shiyu and Joe-Wong, Carlee},

booktitle = {Workshop on Scaling Environments for Agents},

year = {2025}

}

@inproceedings{nourzad2025dr,

title={DR. WELL: Dynamic Reasoning and Learning with Symbolic World Model for Embodied LLM-Based Multi-Agent Collaboration},

author={Nourzad, Narjes and Yang, Hanqing and Chen, Shiyu and Joe-Wong, Carlee},

booktitle={NeurIPS 2025 Workshop on Bridging Language, Agent, and World Models for Reasoning and Planning},

year={2025}

}